Schoolgirls in India are facing a massive shortage of sanitary napkins because schools - a critical part of the supply chain - are closed during the coronavirus lockdown. This has left millions of teenagers across the country anxious.

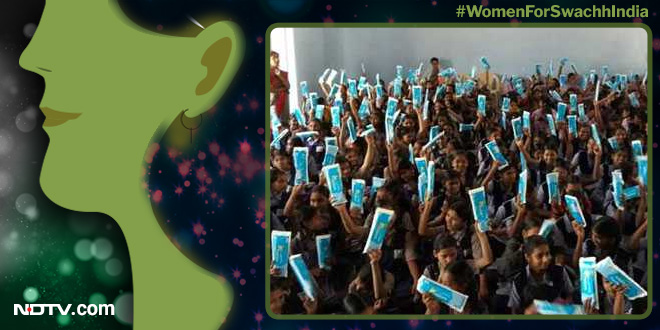

Sanjay Patil : Nagpur Press Media : BBC : 22 May 2020 :For the past several years, Priya has been receiving a pack of 10 sanitary napkins every month from her school.

The 14-year-old, who lives in Badli, a slum in northwest Delhi, attends a state-run school where pads are distributed to all female students in middle and senior school under a government scheme to promote menstrual hygiene.

It's an important campaign in a country where only 36% of its 355 million menstruating females use napkins (the remaining use old cloth, rags, husk or ash to manage the flow) and nearly 23 million girls drop out of school annually after they start their periods.

But, with schools shut because of the lockdown, the supply of pads too has stopped.

"I got my last pack in February," says Priya. "Since then, I have had to buy them from the local chemist. I have to pay 30 rupees ($0.40;£0.30) for a pack of seven napkins."

Priya considers herself lucky that her parents can still pay for her to buy pads. Many of her neighbours have lost their jobs in the lockdown and can't even afford food. Girls in those families have had to start using rags.

Just a few miles from Priya's home in Badli is Bhalaswa Dairy, a slum that's home to around 1,900 families. Madhu Bala Rawat, an activist who lives and works in the area, has also flagged the shortage of sanitary napkins for schoolgirls.

"Periods don't stop during a pandemic. Pads are essential for women, like food. Why does the government ignore our requirement," she asks?

Most girls in the slum, including her 14-year-old daughter, are dependent on the supply from their school because they can't afford to buy sanitary napkins, she says.

"The girls are worried, how will they deal with their periods now? They don't like to use cloth anymore because they have become used to disposable napkins. The government should supply it with the monthly ration."

After Ms Rawat sent out an SOS, Womenite, a charity that works on menstrual hygiene, distributed 150 packs of sanitary napkins in Badli and Bhalaswa Dairy in April.

Harshit Gupta, founder of Womenite, says they have raised funds to distribute 100,000 more packs in Delhi and some surrounding districts in May to coincide with international menstrual hygiene day on the 28th.

"We'll start distributions in the next few days," he told the BBC.

There have been other similar initiatives across India.

One sanitary napkin manufacturer distributed 80,000 pads in Delhi and Punjab.

And police in cities like Bangalore, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Chandigarh, Bhubaneshwar and Kolkata have been roped in to hand them out to residents of slums as well as stranded migrants in relief camps.

On Monday, India's governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) announced it would be giving 600,000 packs to police to distribute among adolescent girls and women in Delhi slums.

But it's not just the cities. The shortage of pads is being felt across the country and the problem is much more acute in semi-urban and rural areas, says Shailja Mehta, who works on issues of adolescents at Dasra, a philanthropic organisation.

"During our conversations with our partners in several states, we heard that only 15% girls had access to sanitary napkins during the lockdown.

"With schools shut, the girls are getting pads only through the community health workers who are handing over whatever little supplies they have."

The problem started when India first imposed a country-wide lockdown on 25 March, and sanitary napkins were not in the list of essential items which were exempt from restrictions.

It was only on 29 March, after reports that chemists, grocery stores and online sites were running out of pads, that the government added sanitary napkins to the list of essentials. The delay caused nearly 10 days of production loss.

"After the government allowed us to operate, it took us another three to four days to restart the factories because we had to get all the required permissions and passes for our workers," Rajesh Shah, president of Feminine and Infant Hygiene Association of India, told the BBC.

Mr Shah says production is still partially resumed because there's an acute shortage of workers who have fled the cities for their villages.

"Only 60% of the factories are operational and not one is operating at full capacity. There is a shortage of workers, factories in 'containment zones' are not allowed to open, and there are massive disruptions in the supply and distribution chain."

There's a massive shortage of sanitary napkins, he says and warns that the situation will get worse before it gets better.

Tanya Mahajan of the Menstrual Health Alliance of India (MHAI), a network of NGOs, manufacturers and experts that works to create awareness about periods, says their partners from across the country have reported "significant disruptions" in supplies, especially in remote rural areas.

"The first to suffer is always the last mile," she says.

"In remote villages, where pads are not available in the local store, people have to go to the nearest town or district centre which could be 10-40kms away. Also at present, there is limited mobility because of social distancing and a lack of public transport."

And most girls may not be comfortable asking men in the family to procure pads for them since periods is a taboo subject not openly talked about in Indian families.

As a result, Ms Mahajan says, many adolescent girls who were dependent on getting supplies from their schools, have started using cloth pads.

Considering that India uses a billion pads a month and the plastic in the disposable pads means they are not biodegradable, campaigners say reusable products such as menstrual cups and cloth pads are a much more sustainable alternative.

Irrespective of what is used, says Arundati Muralidharan of WaterAid charity, it is essential to ensure hygiene - reusable cloth pads must always be cotton, they must be washed properly and dried in the sun before being reused.

It may sound simple, but is not so easy to achieve.

In slums, when all the men are at home because of the lockdown, girls and women may find it difficult to use toilet facilities as frequently as they like and in villages, getting additional water to wash pads and put them out in the sun to dry could be difficult.

"Many of our partner organisations say women and adolescent health has taken a backseat during the Covid-19 crisis and it's important to address that," Ms Muralidharan says.

Menstrual Hygiene Day Facts: Only 36 Percent Of The Women In India Use Sanitary Pads During Periods

Menstruation is normal and a healthy part of life and yet girls and women in India go through extreme struggles to manage their period every month. A large chuck of the Indian population believes this natural cycle to be a ‘curse’, ‘impure’ and ‘dirty’ among other things, courtesy of the ancient myths surrounding menstruation in our country. According to Census 2011 population data, about 336 million girls and women in India are of reproductive age and menstruate for 2-7 days, every month, and yet the topic of menstruation is expected to be a hush affair and kept under wraps of the ‘black plastic bags’, which is given to most of us each time we buy sanitary napkins.

When a girl faces challenges in managing her period in a healthy manner, it can cause a number of problems to her physical as well as mental health. Not only will she be at risk of infection, but her education, self-esteem, and confidence also suffer in a major way. May 28 is observed as Menstrual Hygiene Day globally, so to mark this day, let’s look at some stark facts about menstruation in India that you should know. Period.

1. Only 36 Percent Women Use Sanitary Pads In India

National Family Health Survey 2015-2016 estimates that of the 336 million menstruating women in India about 121 million (roughly 36 percent) women are using sanitary napkins, locally or commercially produced.

2. Sanitary napkins: The Impact on Environment

Most common menstrual hygiene product in India is sanitary napkin which is disposable and they can have an adverse impact on the environment due to the huge amounts of plastics they contain.

Dr. Surbhi Singh, Delhi-based Gynaecologist and a menstrual hygiene activist says,

WaterAid India, a non-profit organisation, stresses on the need to find sustainable alternates to menstrual hygiene practices in India, as it has estimated that of this 121 million girls and women dispose of about 21,780 million pads annually, which poses a major threat to the country’s waste management crisis. The alternatives to sanitary napkins could be menstrual cups, tampons and eco-friendly sanitary pads.

3. What Exactly Happens Due To Poor Menstrual Hygiene?

We often hear that unhygienic period health and disposal practices can have major consequences on the health of women, but what exactly is at risk here? Every person – male or female should be aware of the diseases that could be caused if a woman does not have access to menstrual hygiene products. The issue can increase a woman’s chances of contracting cervical cancer, Reproductive Tract Infections, Hepatitis B infection, various types of yeast infections and Urinary Tract Infection, to name a few.

4. How Informed Are Young Girls Who Are Yet To Menstruate?

A 2016 study titled – ‘Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India’ involving nearly 100,000 girls in India found that almost 50,000 did not know about menstruation until the first time they got their period. The study further explains how many girls even think that they are dying or have caught a horrible disease, the first time they menstruate, due to the pain and blood.

5. Menstruation And Impact On Education

A 2014 report by the NGO Dasra titled ‘Spot On!’ informed that almost 23 million girls in India drop out of school annually, because of lack of menstrual hygiene management facilities, including availability of sanitary napkins and awareness about menstruation. The report further suggests that the girls, who don’t drop out, usually miss up to 5 days of school every month.

23 Million Women Drop Out Of School Every Year When They Start Menstruating In India

It was the occasion of an annual function at a secondary school in Rajasthan’s Dholpur district in May 2017. Manoj Kumar, the district health officer was one of the dignitaries invited to the function. While giving a short speech on the importance of education, Mr Kumar noticed the alarmingly low number of girls present in the crowd of school students. On enquiring further, he was told that many girls drop out of school on reaching the sixth or seventh standard as they reach puberty. In a remote district like Dholpur, a primary school is barely equipped with a functional toilet, let alone something as essential as sanitary napkin dispensers. But more than the infrastructure for young girls in Dholpur, like millions of others in districts, towns and cities across India, menstruation remains a biological event shrouded in mystery and taboo, not to be spoken about openly.

355 million is the number of menstruating women in India, accounting for nearly 30 per cent of the country’s population. Menstruation continues to be a subject of gender disparity in India. Myths about menstruation are largely prevalent, forcing many girls to drop out of school early or be ostracised for the duration of their menstrual cycle every month. A 2014 report by the NGO Dasra titled Spot On! found that nearly 23 million girls drop out of school annually due to lack of proper menstrual hygiene management facilities, which include availability of sanitary napkins and logical awareness of menstruation. The report also came up with some startling numbers. 70 per cent of mothers with menstruating daughters considered menstruation as dirty and 71 per cent adolescent girls remained unaware of menstruation till menarche. A 2014 UNICEF report pointed out that in Tamil Nadu, 79 per cent girls and women were unaware of menstrual hygiene practices. The percentage was 66% in Uttar Pradesh, 56% in Rajasthan and 51% in West Bengal.

Lack of Awareness

Lack of awareness makes for a major problem in India’s menstrual hygiene scenario. Indian Council for Medical Research’s 2011-12 report stated that only 38 per cent menstruating girls in India spoke to their mothers about menstruation. Many mothers were themselves unaware what menstruation was, how it was to be explained to a teenager and what practices could be considered as menstrual hygiene management. Schools were not very helpful either as schools in rural areas refrained from discussing menstrual hygiene. A 2015 survey by the Ministry of Education found that in 63% schools in villages, teachers never discussed menstruation and how to deal with it in a hygienic manner.

Lack of Sanitary Napkins and Adequate Facilities

In a city, availing a sanitary napkin for a woman aware of menstrual hygiene is a normalised process. Not only are sanitary napkins available in pharmacies and grocery stores in cities, they are commercialised via advertisements so that they are treated as any other product. In rural areas, sanitary napkins are found with difficulty. Most girls rely on home-grown or other readily available material, the latter often being unhygienic and unsanitary. Only 2 to 3 per cent women in rural India are estimated to use sanitary napkins. The lack of demand results in storekeepers not stocking up on sanitary pads. This results in women resorting to unhygienic practices during their menstrual cycle, such as filling up old socks with sand and tying them around waists to absorb menstrual blood, or taking up old pieces of cloth and using them to absorb blood. Such methods increase chances of infection and hinder the day-to-day task of a woman on her period.

Impact on Women’s Health

Surveys by the Ministry of Health in 2002, 2005, 2008 and 2012 found out that most problems related to menstrual hygiene in India are preventable, but are not due to low awareness and poor menstrual hygiene management. This resulted in development of some serious ailments for adolescent girls. Roughly 120 million menstruating adolescents in India experience menstrual dysfunctions, affecting their normal daily chores. Nearly 60,000 cases of cervical cancer deaths are reported every year from India, two-third of which are due to poor menstrual hygiene.

Other health problems associated with menstrual hygiene like anaemia, prolonged or short periods, infections of reproductive tracts, as well as psychological problems such as anxiety, embarrassment and shame.

Menstruation is such a taboo subject that many women are ashamed even to seek medical advice if they face any health problems due to menstruation. Unhygienic menstrual conditions often result in women developing health problems which are further aggravated due to their inability to seek medical help on time, said Sahana Bhat, Co-founder of the NGO Sukhibhava which works in the field of menstrual hygiene.

Government Schemes On Menstrual Hygiene

From a ban on advertisements on sanitary napkins in 1990, to a full-fledged feature film, PadMan, on a low-cost sanitary napkin entrepreneur in 2018, India has indeed come a long way. It was eight years back in 2010, when the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched the Freeday Pad Scheme, a pilot project to provide sanitary napkins at subsidised rates for rural girls. The scheme was launched in 152 districts across 20 states and sanitary napkins were sold to adolescent girls at the rate of R

s.

6 per pack of six napkins by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). The estimated cost for the entire scheme was R

s.

70 crore.

A year later, the Union government launched the SABLA scheme across 2015 districts in the country. The scheme aimed at improving health conditions for adolescent girls with menstrual hygiene as an important component. Two years later, under the then ongoing Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan, focus on menstrual hygiene was added as a key component of the sanitation mission. In 2014, the Union government launched the Rashtriya Kishor Swashthya Karyakram, aimed at improving the health and hygiene of an estimated 243 million adolescents. Menstrual hygiene was also included as an integral part of the programme.

Under the ongoing Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, menstrual hygiene has been given high importance. The Swachh Bharat (Gramin) guidelines explicitly state that funds allocated for information, education and communication (IEC) maybe spent on bettering awareness on menstrual hygiene in villages. Adequate knowledge of menstrual hygiene and development of local sanitary napkin manufacturing units is encouraged by Swachh Bharat Mission (rural) and self-help groups are to help in propagating such efforts.

Recently, Union Minister for Drinking Water and Sanitation Uma Bharti said that sanitary napkin, similar to a toilet, is a right of every woman. Reiterating that menstrual hygiene was a key concern for the ministry, Ms Bharti at a recent press conference said that she spoke to Union Minister for Textile Smriti Irani and Union Minister for Woman and Child Development Maneka Gandhi on making affordable sanitary napkins available to women in rural areas.

Looking Ahead: An India With Proper Menstrual Hygiene

“The myths and taboos surrounding menstruation need to be broken down effectively before schemes and incentives make their way to make life better for menstruating women,” said a WaterAid India official.

Conditions for menstruating women in India can only improve when awareness on menstrual hygiene is spread. IEC on menstrual hygiene, under Swachh Bharat Abhiyan or any other state scheme must educate women across all ages on what menstruation is and why the taboos surrounding it do tremendous harm. Simultaneously, sanitary napkins must be provided to menstruating women to ensure that they do not fall prey to age old unhygienic traditions of using cloth, soil or sand. It must be remembered that 88% of India’s menstruating women do not use sanitary napkins. Making sanitary napkins available to over 300 million women and ensuring that they do use these will be a herculean task, and can only be achieved with due cooperation all stakeholders and proper coordination between them to improve the status menstrual hygiene in India.

'Period-shaming' Indian college forces students to strip to underwear

College students living in a hostel in the western Indian state of Gujarat have complained that they were made to strip and show their underwear to female teachers to prove that they were not menstruating.

The 68 young women were pulled out of classrooms and taken to the toilet, where they were asked to individually remove their knickers for inspection.

The incident took place in the city of Bhuj on Tuesday. The young women are undergraduate students at Shree Sahajanand Girls Institute (SSGI), which is run by Swaminarayan sect, a wealthy and conservative Hindu religious group.

They said a hostel official had complained to the college principal on Monday that some of the students were breaking rules menstruating women are supposed to follow.

According to these rules, women are barred from entering the temple and the kitchen and are not allowed to touch other students during their periods.

At meal times, they have to sit away from others, they have to clean their own dishes, and in the classroom, they are expected to sit on the last bench.

One of the students told BBC Gujarati's Prashant Gupta that the hostel maintains a register where they are expected to enter their names when they get their periods, which helps the authorities to identify them.

But for the past two months, not one student had entered her name in the register - perhaps not surprising considering the restrictions they have to put up with if they do.

So on Monday, the hostel official complained to the principal that menstruating students were entering the kitchen, going near the temple, and mingling with other hostellers.

The students allege that, the next day, they were abused by the hostel official and the principal before they were forced to strip.

They described what happened to them as a "very painful experience" that had left them "traumatised" and amounted to "mental torture".

One student's father said that when he arrived at the college, his daughter and several other students came to him and started crying. "They are in shock," he said.

On Thursday, a group of students held a protest on the campus, demanding action against the college officials who had "humiliated" them.

The college trustee Pravin Pindoria said the incident was "unfortunate", adding that an investigation had been ordered and action would be taken against anyone found guilty of wrongdoing.

But Darshana Dholakia, the vice-chancellor of the university which the college is affiliated with, put the blame on the students. She said that they had broken rules and added that some of them had apologised.

However, some of the students told BBC Gujarati that they are now under pressure from the school authorities to play down the incident and not to speak of their ordeal.

On Friday, the Gujarat State Women's Commission ordered an investigation into this "shameful exercise" and asked the students to "come forward and speak without fear about their grievances". The police have lodged a complaint.

This is not the first time that female students have been humiliated on account of periods.

In a very similar case, 70 students were stripped naked three years ago at a residential school in northern India by the female warden after she found blood on a bathroom door.

Discrimination against women on account of menstruation is widespread in India, where periods have long been a taboo and menstruating women are considered impure. They are often excluded from social and religious events, denied entry into temples and shrines and kept out of kitchens.

Increasingly, urban educated women have been challenging these regressive ideas. In the past few years, attempts have been made to see periods for just what they are - a natural biological function.

But success has been patchy.

In 2018, the top court in a landmark order threw open the doors of the Sabarimala shrine to women of all ages, saying that keeping women out of the temple in the southern state of Kerala was discriminatory.

But a year later, the judges agreed to review the order after massive protests in the state.

Surprisingly, the protesters included a large number of women - an indication of how deeply rooted the stigma over menstruation is.

Why are menstruating women in India removing their wombs?

Periods have long been a taboo in the country, menstruating women are believed to be impure and are still excluded from social and religious events. In recent years, these archaic ideas have been increasingly challenged, especially by urban educated women.

But two recent reports show that India's very problematic relationship with menstruation continues. A vast majority of women, especially those from poor families, with no agency and no education, are forced to make choices that have long-term and irreversible impacts on their health and their lives.

The first comes from the western state of Maharashtra where it has been revealed by Indian media that thousands of young women have undergone surgical procedures to remove their wombs in the past three years. In a substantial number of cases they have done this so they can get work as sugarcane harvesters.

Every year, tens of thousands of poor families from Beed, Osmanabad, Sangli and Solapur districts migrate to more affluent western districts of the state - known as "the sugar belt" - to work for six months as "cutters" in sugarcane fields.

Once there, they are at the mercy of greedy contractors who use every opportunity to exploit them.

To begin with, they are reluctant to hire women because cane-cutting is hard work and women may miss a day or two of work during their periods. If they do miss a day's work, they have to pay a penalty.

The living conditions at their work-place are far from ideal - the families have to live in huts or tents close to the fields, there are no toilets, and as harvesting is sometimes done even at night, there is no fixed time for sleeping or waking. And when women get their periods, it just becomes that much more tough for them.

Because of the poor hygienic conditions, many women catch infections and, activists working in the region say, unscrupulous doctors encourage them to undergo unnecessary surgery even if they visit for a minor gynaecological problem which can be treated with medicine.

As most women in these areas are married young, many have two to three children by the time they are in their mid-20s, and because doctors don't tell them about the problems they would face if they underwent a hysterectomy, many believe that it's OK to get rid of their wombs.

This has turned several villages in the region into "villages of womb-less women".

After the issue was raised last month in the state assembly by legislator Neelam Gorhe, Maharashtra Health Minister Eknath Shinde admitted that there had been 4,605 hysterectomies just in Beed district in three years. But, he said, not all of them were carried out on women who worked as sugarcane harvesters. The minister said a committee had been set up to investigate several of the cases.

My colleague Prajakta Dhulap from the BBC's Marathi language service, who visited Vanjarwadi village in Beed district, says from October to March every year, 80% of villagers migrate to work in sugarcane fields. She reports that half of the women in the village have had hysterectomies - most are under the age of 40 and some are still in their 20s.

Many of the women she met said their health had deteriorated since they underwent surgery. One woman talked about the "persistent pain in her back, neck and knee" and how she wakes up in the morning with "swollen hands, face and feet". Another complained of "constant dizziness" and how she was unable to walk even short distances. As a result, they both said they were no longer able to work in the fields.

According to a Thomson Reuters Foundation expose, based on interviews with about 100 women, the drugs were rarely provided by medical professionals and the seamstresses, mostly from poor disadvantaged families, said they couldn't afford to lose a day's wages on account of period pains.

All of the 100 women who were interviewed said they had received drugs, and more than half said that as a result, their health had suffered.

Most said they were not told the name of the drugs or warned about any possible side-effects.

Many of the women blamed these medicines for their health problems, ranging from depression and anxiety, to urinary tract infections, fibroids and miscarriages.

The reports have forced the authorities into action. The National Commission for Women has described the condition of the women in Maharashtra as "pathetic and miserable" and asked the state government to prevent such "atrocities" in future. In Tamil Nadu, the government said they would monitor the health of the garment workers.

The reports come at a time when attempts are being made across the world to increase women's participation in the workforce by implementing gender-sensitive policies.

Worryingly, female workforce participation in India has fallen from 36% in 2005-06 to 25.8% in 2015-16 and it's not hard to understand why if we look at the conditions in which women have to work.

In Indonesia, Japan, South Korea and a few other countries, women are allowed a day off work during their periods. Many private companies also offer similar relief.

"In India too, the Bihar state government has been allowing women employees to take two extra days off every month since as far back as 1992 and it seems to be working very well," says Urvashi Prasad, a public policy specialist at the Indian government think tank, Niti Aayog.

And last year, a female MP tabled a Menstrual Benefits Bill in the parliament, seeking two days off every month for every working woman in the country.

Ms Prasad says there are challenges to implementing any policy in a vast country like India, especially in the informal sector where it needs much more monitoring. But, she says, if a start is made in the formal sector, it can signal a change in mindsets and help remove the stigma that surrounds menstruation in India.

"So what we need is for the powerful organised private sector and the government to take a stand, we need people at the top to send the right signals," she says. "We have to start somewhere and eventually we can expect to see some change in the unorganised sector too."

The Menstrual Benefits Bill is a private member's bill so it's unlikely that it will come to much, but if it does become law, it would likely benefit the women who work in Tamil Nadu's garment factories which will have to implement it.

But such welfare measures rarely benefit those employed in India's vast unorganised sector, which means that women like those working in Maharashtra's sugarcane fields will remain at the mercy of their contractors.

Why are Indian women 'Happy to Bleed'?

Menstruation is generally a taboo topic in India, something that is rarely talked about openly.

But at the weekend, several photographs popped up on my Facebook page of young Indian women holding placards - some made up of sanitary napkins and tampons - with the slogan "Happy To Bleed".

A little bit of research led me to this petition, started by college student Nikita Azad, who was annoyed by the sexist remarks made by the head of the famous Sabarimala temple in Kerala.

"A time will come when people will ask if all women should be disallowed from entering the temple throughout the year," Prayar Gopalakrishnan, who recently took charge of the hilltop temple dedicated to Lord Ayyappa, told reporters earlier this month.

"These days there are machines that can scan bodies and check for weapons. There will be a day when a machine is invented to scan if it is the 'right time' for a woman to enter the temple. When that machine is invented, we will talk about letting women inside," he added.

Ms Azad insists that there is no "right time" to go into a temple and that women should have to right to go "wherever they want to and whenever they want to".

The temple priest's comments, she says, reinforce misogyny and strengthen the myths that revolve around women, and that "Happy To Bleed" is a counter-campaign against menstrual taboos.

Hinduism regards menstruating women as unclean so, during her periods, a woman is not allowed to enter the temple, touch any idols, enter the kitchen or even touch the pickle jar.

Many Hindu temples in India - and also globally - have prominent notices displayed at the entrance telling menstruating women that they are not welcome, and many devout Hindu women voluntarily keep away from temples when they are menstruating.

But the Sabarimala bars all women in the reproductive age from entering the temple.

The temple website explains that as Lord Ayyappa was "Nithya Brahmachari - or celibate - women between the 10-50 age group are not allowed to enter Sabarimala".

The website adds, rather threateningly, that "such women who try to enter Sabarimala will be prevented by (the) authorities" from doing so.

Ms Azad says "we don't believe in religion that considers half the world impure" and that theirs is "not a temple-entry campaign" - it's "a protest against patriarchy and gender discriminatory practices prevalent in our society" and that they are fighting against sexism and age-old taboos.

Since its launch on Saturday, #HappyToBleed has received a lot of responses, especially from young urban Indian women.

"More than 100 women have posted their photographs on Facebook holding banners and placards, with catchy slogans, and many more have shared these photos on their timelines," Ms Azad told the BBC.

The campaign has also been picked up by many people on Twitter who have written in with messages of support.

Some, however, have also wondered how women can be "happy" to bleed since periods can often be pretty painful.

"We are using happy as a word to express sarcasm - as a satire, to taunt the authorities, the patriarchal forces which attach impurity with menstruation," Ms Azad explains.

"It may be painful, but it's perfectly normal to bleed and it does not make me impure," she adds.

0 comments: